By Emily Miller

Step into the city of Wilkes-Barre and you will notice the remnants of a period long passed. The roads, once covered in railroad tracks, have been paved over, although not all too well. The rail station which once bustled with people is now a shell of what it once was. Its walls crumble, and what is left of it is now covered in graffiti. Once upon a time, that train station would bring in people from around the country. Once upon a time, this city was known for its wealth, wealth that was built upon the backs of thousands of immigrants. These immigrants, the work slaves of this city, had the whole country at a standstill once upon a time.

We have all been told the stories of coal mining in this area. We even bear witness to the fruits of this treacherous labor through our grand courthouse which stands proudly in the city of Wilkes-Barre. The houses that some of us may live in may have once belonged to a family of coal miners, and the land it sits on once trekked upon by men on their way to spend hours underneath the soil.

Most when they think of coal mining in this area go back to the Knox Mine Disaster, the end of coal mining for Pennsylvania. There are other times when the production of coal had been stopped in this area, however.

The year is 1902

The sitting president is Theodore Roosevelt, who was sworn into the presidency after the assassination of William McKinley. As was a custom with most of those in office at the time, McKinley had had a tendency of siding with big business, his ticket into his second term being bought by men such as, JP Morgan, Andrew Carnegie and John Markle. It is men like John Markle, who so poorly treated his miners, who would eventually catch the eye of Roosevelt, causing him to be the first president involved in the affairs of industry to fight on the side of the worker.

Voting during this time, voting done by coal miners specifically, was not as climactic as is the scene today. Most, if not all, coal miners would vote on the side of the Republican nominee, as opposed to the robber barons of the time, who favored the Democratic nominee. Theodore Roosevelt was William McKinley’s Vice President. Roosevelt was a Republican, although today he may be seen more so as a liberal progressive. He was a man of the people who wanted to see things done in this country, not only for big business, but for the working man as well. He wanted reform and a great change to occur and would stop at nothing to make these things possible. Here is where we see the vote of the American people truly starts to matter, with the pause in production of anthracite coal. Why is this where our voice starts to matter? Our voices are finally heard during the 1902 coal strike because we the people of Pennsylvania had the entirety of the United States at a standstill.

With the dawn of the industrial revolution, companies such as the railroads and American steal were taking off, but these companies could not fuel themselves on their own. Anthracite Coal. One of the best of its kind. It burns a lot easier and cleaner than normal coal, and it is in abundance in this valley. Anthracite coal was used to fuel homes and businesses across the country. It was used to feed the stokers of train cars and in the production of steal. But like all good things that revolutionized this country at the time, it became a monopoly, praying on the weaker man to line the pockets of business tycoons like John Markle.

The year is 1902

You are a member in the crowd that has come to hear the current proceedings being posed to the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission. The disgust and dismay over the situation are palpable through the air. The child that stands before you is but only twelve years of age, yet it seems as if he has already dealt with a lifetime of hardship. His name is Andrew Chippie, and the proceedings that have brought him here today would change his life and his family lives’ for forever.

Andrew Chippie was the son of an immigrant coal miner, who had come to the United States for more opportunities. Like every other family of a coal miner, Chippie’s family lived in the housing provided by the mining company. The same company that also sold to them their supplies for mining, food for their families and the clothes on their backs. Seems almost too good to be true, which indeed it was. The housing that was offered and the supplies that were sold to the miners and their families were provided at extremely high rates. These jacked up rates made it so that with the little money the miners made, they would never be able to leave this level of poverty. The houses that they lived in were mere shacks, housing whole families including grandparents, aunts and uncles and cousins. Families did what they could to afford the high prices of the mining companies. Many families like the Chippie’s were so in debt with these companies that they could never escape the mines, which brings us back to Andrew Chippie’s story and why he stands before the Commission.

Andrew Chippie’s father died during a mining accident, leaving behind his wife and three sons. Chippie, who had only been in school for roughly a year of his life, decided to drop out to pay off the debts of his father to the Markle Company. He endured strenuous work for up to ten hours a day as a breaker boy, making only $0.04 an hour. As the months passed, the families debts rose and rose, until finally John Markle had them kicked out onto the streets, which brings us here today. You cannot feel anything but hatred towards this man, who has ruined families all over the area, and who has lined his pockets with the labors of these dead men walking.

Chippie’s family was part of the second wave of immigrants to arrive here in the United States for the purpose of coal mining. The first immigrants were Welsh and English technical groups who had prior experience in the mines. The mining companies would need more men than the ones that had come from these two groups, however. With immigrants from across the world coming to the United States, there were plenty of men looking for work to fill these positions. Men from Ireland, Poland, and Italy, to name a few, were quick to snatch up these jobs and enter the mines. Little did they know that back breaking work with twelve hour working days, and things such as black lung awaited them down in those mines.

The year is 1902

It has only been two years since the first anthracite coal mining strike, but in those two short years more unrest has arisen. The men are tired. They are tired from those twelve-hour workdays. They are tired of the unsafe conditions of the coal mines and being cheated of their weights, and they are tired of making little to no money for the work that they put in. It is men like Andrew Chippie’s father, who lost their life due to company negligence, that these coal miners strike for. The year is 1902. The year of the anthracite coal mining strike.

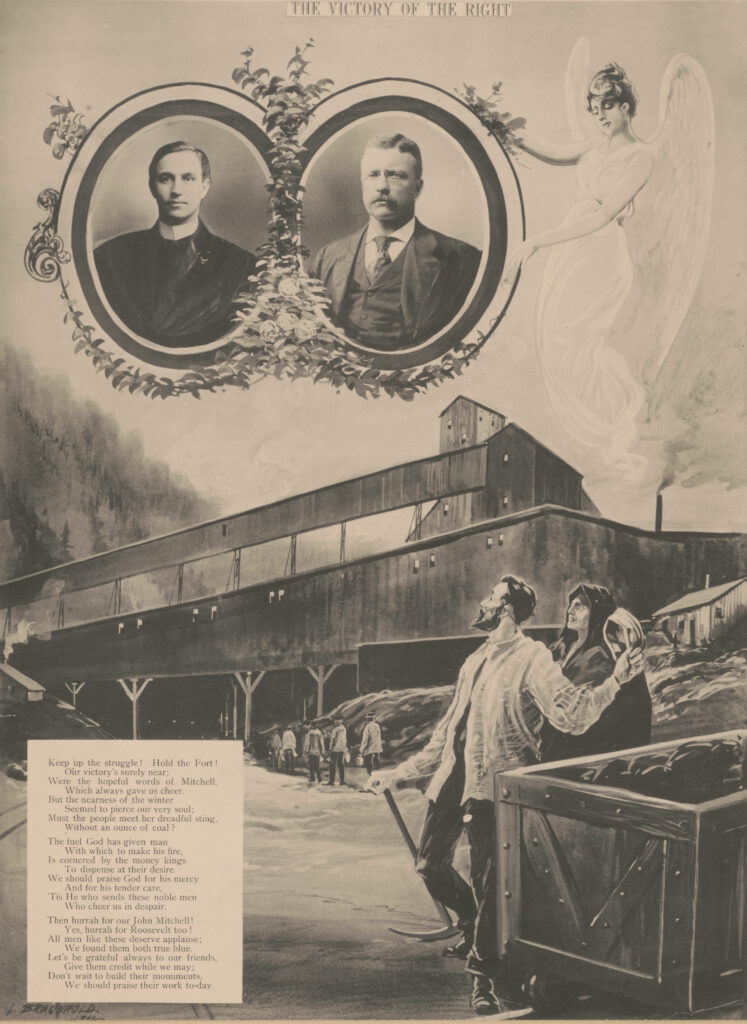

For years, the United Mine Workers of America had fought for fair wages for coal miners, most of their pleas falling to deaf ears. Finally, the men had had enough. Under the leadership of John Mitchell, president of the United Mine Workers of America, the men took to the picket lines.

Some of the officers of the coal mining union opposed the idea of a strike. They [the officers] weighed the options that the men had, and the results appeared grim. The chances of the coal miners succeeding in their strike were slim to none. They feared the consequences that the coal miners would face if the strike were to go into the summer months, and possibly even farther, but the men persisted, not having their demands met from the 1900 coal strike. Some of their demands included the following: an increase of wages by 20 percent to the miners who are paid by ton of coal, that work days be cut down to 8 hours, and that a ton of coal constitute 2,240 pounds. No compromise could be made, however, and the robber barons only persisted in their heinous cruelty. The coal miners were angered by this as their conditions only worsened. The men of Pennsylvania had nothing left to lose.

May: the men go on strike. John Mitchell, who was looking to make a difference within the Pennsylvania anthracite coal mining community, led some 145,000 miners to peacefully protest.

John Mitchell rose to his presidency of the United Mine Workers in the year 1898. Under his guidance the Union flourished, helping thousands of miners across the country. When he finally made his way to Pennsylvania, there was a great race for the purchase of anthracite coal mines. This great race took place during the year 1900, the same year as the first anthracite coal strike. Most of the mines in this area were owned by the major railroad companies, but independent companies were looking to have a hand in the lucrative business as well. Pennsylvania, specially this area, is one of the only places where anthracite coal can be found, and in these robber barons “get rich” schemes, many lives were put on the line for massive amounts of wealth.

The year is 1902

The strike, which began in May of 1902, has gone on for several months. The men are restless. They are concerned for the wellbeing of their families, yet they persist in hopes of just wages and better working conditions. Their protest has remained peaceful, as Mitchell had desired. To keep up with the needs of the men and their families, Mitchell set up a fund for benefactors to send in money and supplies. That money would provide for hundreds of families, keeping them alive until the end of this ordeal.

October: It has now been five months since the dawning of the strike, and neither side has budged to make a compromise. With winter rapidly approaching, the entirety of the United States is starting to feel the impact of this coal strike. The people are angry. How are they supposed to heat their homes and businesses? How will they survive the cold winter months?

With the US feeling the impact of Pennsylvania’s battle of the opposing classes, President Theodore Roosevelt is advised to step in. Now, instead of siding with the robber barons, Roosevelt decides to invite the leaders of the union to a meeting, a move that had never been made before by any active president.

This hard-fought victory for the miners, which was finally conceded in March of 1903, changed the tides of the working class. No longer was the business tycoon the victor. No, the working class, our ancestors, changed the tides of American history, with the help of John Mitchell and Theodore Roosevelt.

Step into the streets of Wilkes Barre and you may just see the remnants of a history past. The streets, once filled with coal miners, who for five months stopped one of the most powerful industries in the United States at the time, hold the stories of a city that once was. The mines, although closed for the past several decades, remind us every day of how this part of Northeastern Pennsylvania was put on the map. This area was built on the backs of a working-class people, and it remains the same. Our thoughts and opinions, although seeming to feel insignificant, still hold merit. This forgotten part of Pennsylvania which once heated the entirety of the United States to this day holds the power of the vote.

DEDICATION

I would like to thank Mr. William Lewis of the Luzerne County Historical Society for providing me with the research that was needed to write this paper. Without groups like the Historical Society we would forget all the things that make this area what it is today.

Works Cited

Andrews, Evan. “The Assassination of President William McKinley.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 6 Sept. 2016. www.history.com/news/the-assassination-of-president-william-mckinley

Cunniff, M.G. “The Real Issue of the Coal Strike.” EHISTORY. ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/gildedage/1902AnthraciteStrike/content/RealIssue

“Coal Miner’s Son: The Coal Strike of 1902 and Andrew Chippie.” The History Dr, 2 Feb. 2018. historydr.com/1902-coal-strike-helps-interpret-history/

Dessem, Matthew. “Heartwarming! When His Father Died in a Coal Mine, This 12-Year-Old Went to Work in the Same Coal Mine.” Slate Magazine, Slate, 11 June 2019. slate.com/culture/2019/06/andrew-chippie-heartwarming-markle-breaker-boy-debt.html

Lloyd, Caro. Henry Demarest Lloyd: 1847-1903 A Biography. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912.

Wiebe, Robert H. “The Anthracite Strike of 1902: A Record of Confusion.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 48, no. 2, 1961, pp. 229–251. JSTOR.

Wright, Carroll D. Report To The President On Anthracite Coal Strike. Washington, Department of Labor, 1902.